The Origins and History of Halloween

When we think of Halloween, we can’t help but remember that great masterpiece, ‘The Nightmare Before Christmas’!

Since its release years ago, this film has captured the hearts of fans who take advantage of every Halloween and Christmas to watch it repeatedly. By the way, are you Team ‘I watch it on Halloween,’ Team ‘I watch it on Christmas,’ or ‘Team I watch it in both cases’?

Anyway, when it comes to one of the most well-known and celebrated festive traditions globally, I couldn’t miss the opportunity to share some more historical trivia about the origins of this ancient celebration beloved by young and old alike to this day!

So, as usual, get your costumes and jack-o’-lanterns ready… the land of Halloween and Jack Skellington await us!

‘All Hallow Even

Halloween is a contracted form of ‘All Hallow Even,’ meaning the eve of All Saints’ Day. Today, when we talk about this holiday, the first thing that comes to mind is a series of children dressed as monsters, witches, or zombies, going around for the classic ‘trick or treat’ or carving pumpkins (the jack-o’-lanterns) with wicked grins and sinister laughter to decorate their homes and gardens.

In reality, however, Halloween has a much older origin, dating back to the ancient Celtic people and the festival of Samhain celebrated in Britain and Ireland.

The Samhain

Samhain was a pagan festival, to be precise, a kind of Celtic New Year, whose roots go back over a thousand years. Among these populations, October 31st corresponded to our December 31st, and November 1st to our January 1st.

Furthermore, the name means ‘end of summer’; Samhain, besides being a sort of New Year, marked the end of the summer harvest season and the arrival of the cold and lengthy winter period.

But what does all this have to do with the living and the dead? The Celts believed that during this time of year, the veil between the world of the living and that of the dead became thinner, allowing the deceased to return to the earth, wandering in search of familiar faces, places, and homes. Moreover, those who had died in the past year and had not yet moved on could interact with the living during this period.

The Rituals of Samhain

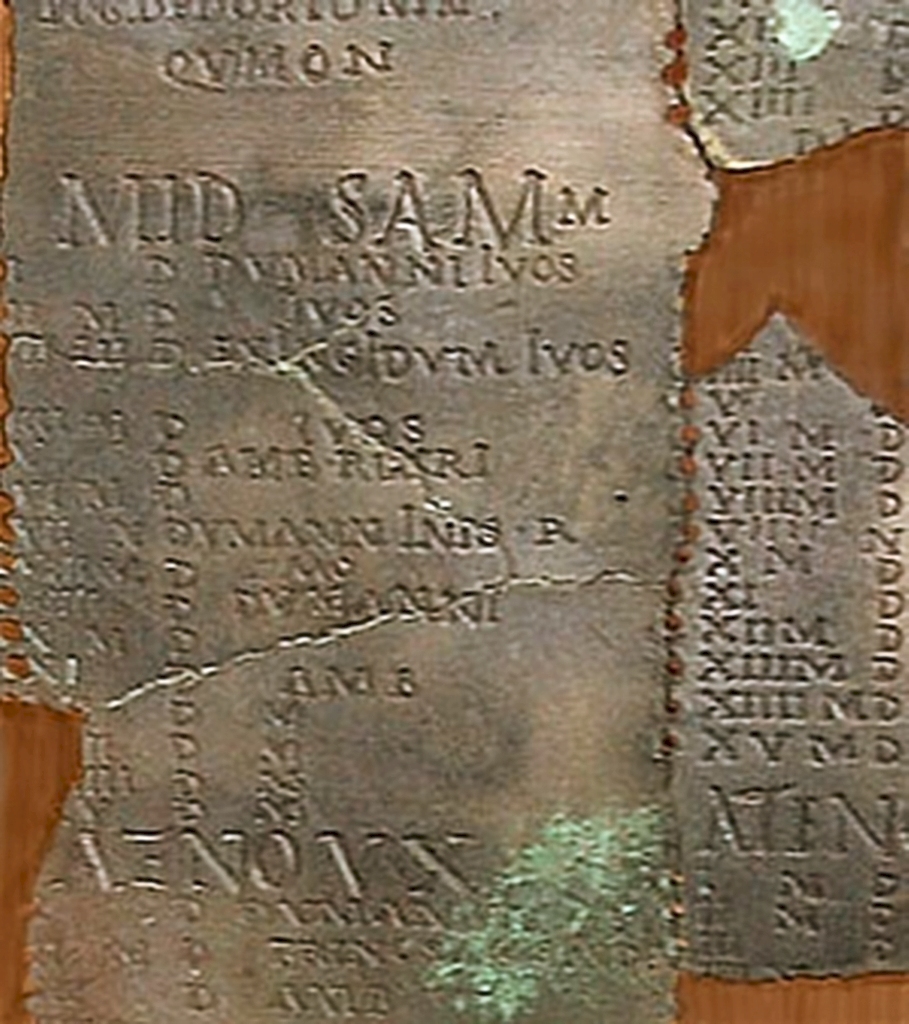

According to the few surviving sources (mostly thanks to the studies of Irish monks), the rituals of Samhain were diverse, but the primary custom was to light a bonfire on October 31st on the Hill of Ward in the Irish county of Meath. This hill was formerly known as the Hill of Tlachtga, in honor of the mythological druid Tlachtga, the daughter of the druid Mug Ruith, to whom part of the festivity and the bonfire were dedicated.

The start of the celebrations was marked by the lighting of this bonfire and another in response, set ablaze on a hill opposite called the Hill of Tara. It’s worth noting that today, this site houses a Neolithic origin site with a monolith known as the Lia Fail, the Stone of Destiny.

From that moment onward, the celebrations commenced, which included stocking up on supplies for the impending winter, the slaughtering of livestock, and the tossing of bones into the sacred bonfires in honor of the deities. During the festivities, many hoped to encounter their deceased loved ones and, to welcome them prepared food and provisions. Besides the dead, it was believed that elves, fairies, and malevolent spirits might also make their appearance. To protect themselves from the latter, people would “disguise” themselves by covering their faces with ashes from the bonfires or wearing costumes made of animal heads and skins, so as not to be recognized by unwanted spirits, only by those of their loved ones.

Another typical Samhain custom was divination. According to the Celts, the thinning of the veil between the world of the living and that of the dead made it easier for Druids and priests to make predictions and prophecies about the future, such as matters related to marriage, health, or even death itself.

The Ancient Romans Arrive

In the 1st century AD, the Roman Empire arrived and conquered much of the territories of Celtic populations. It was during this time that the Samhain festival, over the years, blended with some Roman celebrations such as the Lemuria, Feralia, and festivities in honor of the goddess Pomona.

The Lemuria was a nighttime festival celebrated on May 9th, 11th, and 13th to appease the wandering souls of the deceased and keep them away from the household (according to the Romans, Lemures were precisely the souls of the dead).

The Feralia was part of celebrations called Parentalia, a sacred period dedicated to the worship of the dead held from February 11th to February 21st. The last day was the most solemn of all, and these celebrations were precisely called Feralia because they were public festivals and differed from the rest of the days when commemorations in honor of the deceased were private. It was during the Feralia that the living remembered the dead by visiting their graves and leaving offerings such as grains, salt, bread soaked in wine, and flower crowns.

According to some studies, it appears that Pomona, the goddess of fruits often depicted with baskets and cornucopias filled with fruits and apples, was also honored during these celebrations.

According to some, the classic Halloween game of ‘apple bobbing,’ in which one must attempt to bite into apples floating in a tub of water with hands tied behind the back, is believed to be a result of the merging of the Roman festivities and the cult of Pomona with Samhain.

Christianization

As the centuries passed and Christianity arrived, many ancient rituals, festivals, and sacred sites were naturally Christianized and incorporated into a new form within the new order. This also happened to Samhain and all the pagan festivals of ancient Rome. In the 7th century AD, Pope Boniface IV established the feast of All Saints’ Day on May 13th, during which all the saints would be celebrated. Later, Pope Gregory III moved the date from May 13th to November 1st. According to some scholars, this change was made specifically to Christianize and supplant the pagan festivities of Samhain, transforming them into those of All Saints’ Day.

From then on, new traditions were added to the old ones, which, however, never completely disappeared. The night of All Saints’ Day essentially became a night of prayer and vigil to honor the saints on November 1st.

Bonfires continued to be lit, though in honor of Christian saints rather than pagan gods, and this celebration was still used to mark the change of the season.

Over the years, new traditions were also introduced, such as the practice of ‘souling.’ According to this custom, the poor in villages and cities would knock on the doors of houses, begging for prayers for the deceased in exchange for ‘soul-cakes’ or ‘soul mass cakes’—shortcrust pastry cookies with spices. This custom is likely the precursor to the modern ‘trick or treat’ tradition.

However, the arrival of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century put an end to the religious aspect of the holiday among Protestants, though it continued as a secular celebration in the United Kingdom.

Arrival in the United States

Halloween, to this day, is a global holiday, second in popularity only to Christmas. However, in the end, despite its origins in the forests of ancient Celts and its journey through the hands of Romans and Christians, it eventually landed on the shores of the United States, along with the ships of the colonists, and here it became one of the most celebrated and well-known holidays, to the extent that it became a symbol of an entire nation.

It was the early English and Irish settlers who brought these ancient traditions with them. However, at least among the early settlers, such as the Puritans in New England, holidays like Halloween, Christmas, and Easter were banned because they were too closely tied to ancient pagan rituals.

It was the Irish who revived and introduced the All Saints’ and All Souls’ Day celebrations, including the ancient rites and traditions described above, bringing them to the New World and enriching them with new traditions like that of the Jack-o’-Lantern, the practice of carving pumpkins, the history and legend of which you can read in one of our articles here.

Since then, Halloween has become what we know today, continuing to preserve many of the ancient customs and remaining a holiday rooted in transformation. Not only in the tradition of disguising oneself to avoid recognition by malevolent spirits but also to mark the transition from one season to another and to commemorate saints and the deceased. These are all traditions that, as we have seen, are very, very ancient.

Halloween with a Thousand Faces

Certainly, there is still much to say about Halloween and its customs, particularly because its celebration is so diverse and extensive that it has incorporated over the centuries a multitude of different customs and faces.

This is how we find similar celebrations to Halloween everywhere, such as the ‘Día de los Muertos’ in Mexico, as masterfully depicted in the Pixar film Coco; or the Qingming Festival in China, and the ancient Walpurgis Night typical of Northern European countries (mentioned in the classic ‘Fantasia’), just to name a few.

Those who think of Halloween today may only see what has been more recently portrayed, but it’s fascinating to know that behind traditions like these lies the long journey of entire peoples, filled with beliefs and rituals that have reached us from so far back in time, after countless adventures and changes. It’s precisely these ancient traditions that have inspired films and masterpieces like ‘The Nightmare Before Christmas’ or ‘Hocus Pocus,’ to name just a few Halloween-themed movies.

And what about you? Do you enjoy celebrating Halloween? If you liked the article, let us know by commenting on our social media channels!

Sources:

- https://www.worldhistory.org/trans/it/2-1456/la-storia-di-halloween/

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Halloween

- https://www.history.com/topics/halloween/history-of-halloween

- https://www.treccani.it/vocabolario/halloween/

- https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/feralie_%28Enciclopedia-Italiana%29/#:~:text=feralia%2C%20propr.,ultimo%20giorno%20delle%20feste%20parentali.

- https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/lemuri_%28Enciclopedia-Italiana%29/

- https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/pomona_res-71a02899-e1d1-11df-9ef0-d5ce3506d72e/