The Hunchback of Notre Dame and the History of the Feast of Fools

As Clopin sings in a famous scene from ‘The Hunchback of Notre Dame’:

"It's the day the devil in us gets released It's the day we mock the prig and shock the priest Everything is topsy turvy at the Feast of Fools."

The scene in question depicts one of the undoubtedly most famous and narrated festivities of the medieval period: the renowned Feast of Fools!

The Feast of Fools is one of the focal points of the well-known Disney classic. It is the moment when the true meaning of the movie is concentrated, and all the main characters come together and interact, giving rise to one of the most significant yet also dark plots in Disney, due to the difficult themes that are addressed.

Indeed, between racism, marginalization, and death penalties, we find ourselves facing a very audacious experiment by the Mickey Mouse production company. I have no difficulty saying that knowing Uncle Walt, he would have been surprised and proud if he were still alive!

The seductive and revolutionary beauty of Esmeralda, the crowd that applauds you one moment and betrays you the next (a classic Jesus and Barabbas switcheroo), the dark judgment of power exerted by Frollo, and finally the diversity of Quasimodo, who unwittingly becomes a victim of it all. All these recurring themes throughout the film come together precisely during the representation of the Feast of Fools, making this celebration the focal point of the movie.

But historically, what were the origins of this feast, and what exactly was it about?

In today’s article, we attempt to explain just that. So, get ready with your ugliest masks and join us for one of the most famous celebrations of ancient times!

The Origins of the Feast: The Saturnalia

Now, first and foremost, know this: when it comes to festivals and celebrations, you can be almost certain that pagans or, at the very least, the ancient Romans or Greeks are involved. The Feast of Fools although it was a typically medieval celebration, was nothing more than a Christian adaptation of one of the most famous and popular festivals of ancient Rome: the Saturnalia, which was celebrated from December 17th to 23rd in honor of the god Saturn. Without delving too deep, it’s enough to know that here too, as later with the Feast of Fools, one of the focal points was the reversal of social roles.

During the Saturnalia, indeed, slaves were granted the utmost freedom to express themselves and behave as they pleased, while masters would host banquets for them, exchanging gifts of all kinds and values.

During these festivities, the “Princeps Saturnalicius” was elected, a sort of king of the feast who had the task of directing the whole affair, to put it simply.

It is clear, then, how the Feast of Fools is a direct remake and adaptation of this ancient custom.

From Ancient Rome to the Middle Ages

Just like the Saturnalia, the Feast of Fools, known in Latin as Festum Fatuorum or Festum Stultorum, was celebrated in December between Christmas and Epiphany, specifically around New Year’s, and was also called by other names such as the “Feast of the Ass,” “Feast of the Innocents” or “Children,” or even “Feast of the Deacons.” It was organized by the clergy and held throughout Europe, particularly in France. Everyone participated, men, women, teenagers, and children, including the organizers themselves, who were members of various orders within the ecclesiastical clergy, such as deacons, priests, penitents, acolytes, and subdeacons. The Feast of Fools was, in fact, an authentic ecclesiastical celebration.

Each of them had a specific day dedicated to their festivities, starting from Saint Stephen’s Day onward, and the most unique and “foolish” celebrations were reserved for the subdeacons’ feast days, which took place between New Year’s and Epiphany.

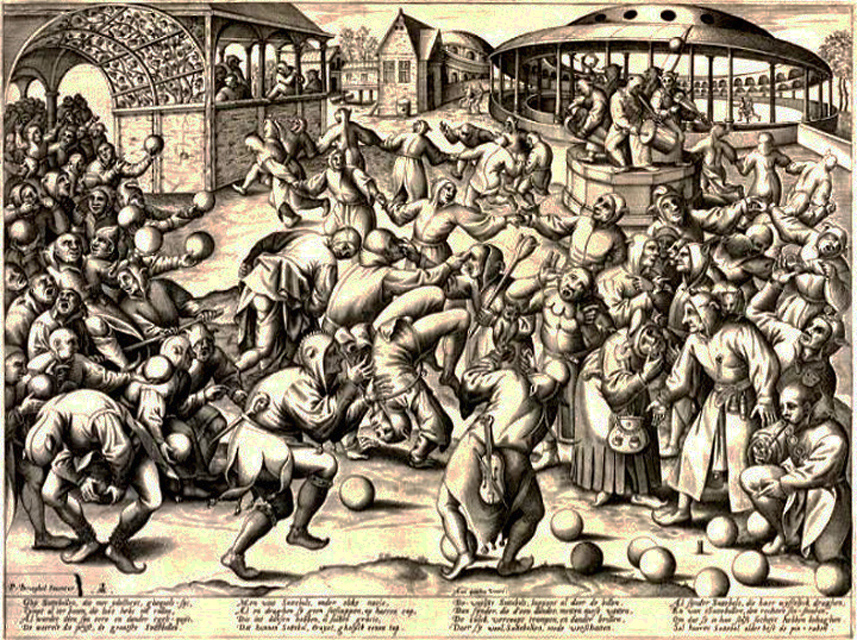

The festivities involved not only masks, disguises, dances, banquets, and gifts of all kinds but also true religious parodies.

Pranks were played, and in other words, this feast was used as a way to overturn the traditional and rigid order that everyone had to abide by, especially for those young people who, subjected to strict ecclesiastical discipline, felt free to express themselves during those days without the risk of punishment or, worse, persecution.

In practice, it was a complete reversal of society and normal social roles: often, priests and clerics would dance, sing obscene songs, dress up as women, madmen, monsters, and beasts, wear clothes backward, and burn the soles of their shoes instead of incense (?!?! I can’t explain this one either because I’m still trying to understand it myself, but considering it’s the Feast of Fools, there’s not much to explain).

On the contrary, beggars, the poor, sometimes even children, and in short, all those considered marginalized by society would dress up as friars or bishops, and among themselves, they would elect the so-called “Pope of Fools,” also known in Latin as Episcopus Puerorum or Innocentium (or King of Fools, as our dear Quasimodo is called in the film), who had the task of bestowing “blessings.” Dressed as a mock bishop, he was the true lord and head of the entire celebration. Just like Quasimodo in the film, he would be placed on a carriage and paraded through the city streets, accompanied by the clerics who would throw rubbish at passersby, and everyone was obliged to prostrate themselves at his feet to receive the “blessing.”

One very important thing that is also evident in the film is that the Feast of Fools was a celebration in which one could not abstain from participating. It is no coincidence that Frollo, who despises and does not tolerate this feast, participates in it, albeit reluctantly, and he does so because he is forced to, as he explains. Historians report that those who showed reluctance or opposition were immediately sanctioned and reprimanded.

Ultimately, the feast was driven by the desire of the marginalized to exact revenge on the established order that used and exploited them, much like how Frollo treats Quasimodo, attempting to punish or subjugate them to his own will, just as Frollo tries to do with Esmeralda.

The Feast of Fools was the retaliation of these marginalized individuals, and that is why it is Quasimodo’s favorite day.

For these reasons, over time, the festivities became a blatant mockery of Christian morals and worship, as well as a means to contest and overturn the established order. In other words, they began to be seen as a danger, leading to repeated condemnation, prohibition, and sanctions by the Council of Basel in 1431. However, it was only in the 16th century that they began to fade away completely.

From Spectators to Actors

The Hunchback of Notre Dame portrays, in a remarkably accurate and straightforward manner, all the most important aspects of this feast.

I must say that, in my opinion, it was not easy at all to bring one of the most famous and unique literary works of all time to the big screen as an animated film. However, it must be said that Disney did an excellent job. And even though The Hunchback of Notre Dame remains one of the darkest and most challenging Disney animations to understand and comprehend, especially for a young audience, it is undoubtedly one of the Disney works that have achieved great artistic, cultural, and historical success.

The part of the Feast is particularly emblematic in every aspect, starting from the beautiful scene sung by Clopin, which meticulously presents the purpose of the feast, to the scene where Quasimodo, the king of fools, is hailed by the crowd and finally, filled with joy, he is moved by feeling free to be himself.

There lies the entire core and historical-cultural significance of the Feast of Fools, a moment when the poor and marginalized can finally stand on the same level as others without being punished for it. They can move from being spectators to becoming actors.

However, equally emblematic is the scene in which, seconds after being acclaimed, Quasimodo is mocked and cruelly mistreated by the same crowd that had lifted him, starting with the soldiers under the command of his master, Frollo.

Just as symbolic and powerful is the scene in which Esmeralda approaches poor Quasimodo and shouts “Justice!” against the established order and its cruelty. But it is too late; the Feast of Fools has come to an end, and the established order has returned to its natural state. The marginalized return to being just that, spectators and not actors.

It’s a bit like Cinderella’s spell with the glass slipper. Midnight arrives, and everything is over, indicating that a feast alone is not enough to overturn the established order.

But, just as Cinderella keeps the slipper and uses it to free herself, the feast can be a starting point, and it is for Quasimodo. From there, he will set out to free himself and finally live a life as an actor and no longer as a mere spectator.

Sources:

- https://bit.ly/39Yv7I5

- https://bit.ly/37DMcE4

- https://bit.ly/36X8i5v

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Feast-of-Fools

- https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06132a.htm

- https://bit.ly/39YvFO9

- https://bit.ly/3gr2l3O