Scarlet Witch and the History of Witches in Europe

“WandaVision” has recently made its debut, and we already had the opportunity to see Wanda’s magic in action in a different way than the one we have seen in the MCU so far. Undoubtedly, Wanda’s powers are something extraordinary and formidable, making her name “Scarlet Witch” quite fitting.

And for this reason, today we will talk about the history of witches.

Witches for Every Taste

These days, when we think of witches, our imagination spans from the old hag from “Snow White” to the sweet Glinda from “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.” Generally, however, the idea of a witch or a warlock tends to be associated with something occult and dark, wild and chaotic, and sometimes even demonic, though not necessarily evil, while more benign and controlled aspects are associated with the concept of wizard.

So why was the name ‘witch’ chosen for a superheroine? There are three reasons. The first and most important is that the name “Scarlet Witch” is incredibly powerful and sounds much more epic than ‘sorceress.’

Evil Mutants and Magical Powers

The second reason that justify the name is her origins: Wanda Maximoff and her twin brother Pietro were initially introduced as villains. They first appeared in X-Men #4 in 1964 as members of the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants, and only a year later, they redeemed themselves by joining the Avengers, just as it happened in the MCU, where they first appeared as followers of Hydra and then of Ultron before ultimately siding with the Avengers. Being born as an enemy of the good guys, the name ‘witch’ was therefore much more fitting.

The third factor is her superpowers. Today, Wanda is one of the most powerful characters in the Marvel Universe, and her magic is referred to as “chaos magic”, granting her the ability to alter probability and space-time reality. However, in the MCU, her powers are more focused on telekinesis, telepathy, and mind control. All these powers are traditionally associated with witches, whether for good or evil.

Magic in Greece and Rome

People considered to possess magical powers can be found in all civilizations and throughout history, but let’s take a look at how the belief in women practicing magic associated with demons originated in Europe.

In the Greco-Roman world, magic was considered normal. The Goddess of Spells, Hecate, was worshipped in various cities, and her statues could be found at every crossroad, protecting travelers. Cities and governments regulated magic like any other aspect of civilized life. For example, the Roman dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla, in 81 BC, passed the lex Cornelia de sicariis et veneficis, a law against crimes committed by armed individuals (sicariis) and those carried out through more sophisticated means like poison or magic (veneficis). This meant that specific actions or practices were condemned, not magic itself.

The Strigae

For the Greeks and Romans, a witch was not an evil woman endowed with magical powers. They certainly had women with such characteristics, as we can see with figures like Medea and her penchant for murder, but they used other terms to define them (such as “maleficus/a,” for example).

For them, witches (streghe in italian), or rather, the strigae, were not women but actual demons who were part of Hecate’s retinue. The Goddess of Spells was a Chthonic deity, meaning she was associated with the underworld, and psychopomp, capable of traveling between Hades, Olympus, and the earthly realm at will. During her nocturnal excursions, she was accompanied by a host of demons, including infernal dogs, lamia, empusae, and, indeed, strigae. The strigae would suck the blood of newborns, sometimes even kidnapping them, and, along with the rest of the retinue, they made an infernal noise with their screeches.

It is no coincidence that the Greek name for the screech owl is “stryx”. You might be surprised to think that this feathery nocturnal predator was associated with Hecate’s retinue, but you will reconsider once you hear its call, which is eerie when heard on a moonless night. The call of the male screech owl resembles a howl, while that of the female is a sharp screech. If you have never heard them and are curious, you can listen to both calls here.

Christianity and the Middle Ages

With the advent of Christianity, all magic and pagan worship practices were banned and considered demonic. During the High Middle Ages, there were various regulations against pagan cults, particularly the Canon Episcopi by Regino of Prüm, which legislated against both male and female magic practitioners and women who believed they followed the goddess Diana at night.

It is important to remember that Diana and Hecate were often associated since both were linked to the moon. This association is the reason behind the black cat-witch association, as cats were sacred to the goddess of the hunt (if you are interested in the topic, we refer you to our article on Bast and Black Panther). In the Middle Ages, pagan gods and numerous mythological creatures were transformed into devils and demons. Since people could no longer distinguish the subtle differences among them, everything was reinvented. It was in the 11th century that the strigae, now called witches, were considered mere women, as seen in King Coloman of Hungary’s decree against belief in witches (1074-1116). However, with witches being perceived as allies of the devil, systematic persecutions began.

The Witch Hunts

In the comics, the Maximoff twins are saved by Magneto when the people of their hometown want to burn Wanda at the stake because of her witch powers.

Similar scenarios were common in late medieval and early modern Europe. The period of intense witch-hunting activity spanned from 1430 to 1780, reaching its peak between 1560 and 1630. The persecutions were primarily driven by the desire of rulers, bishops, and the general population to find a scapegoat for the chaos created by religious Counter-Reformation, worsening climate, war, and the resurgence of deadly waves of plague. Witch hunts were particularly violent in Germany and other Nordic countries, leading to the prosecution and execution of countless women, commonly burned at the stake.

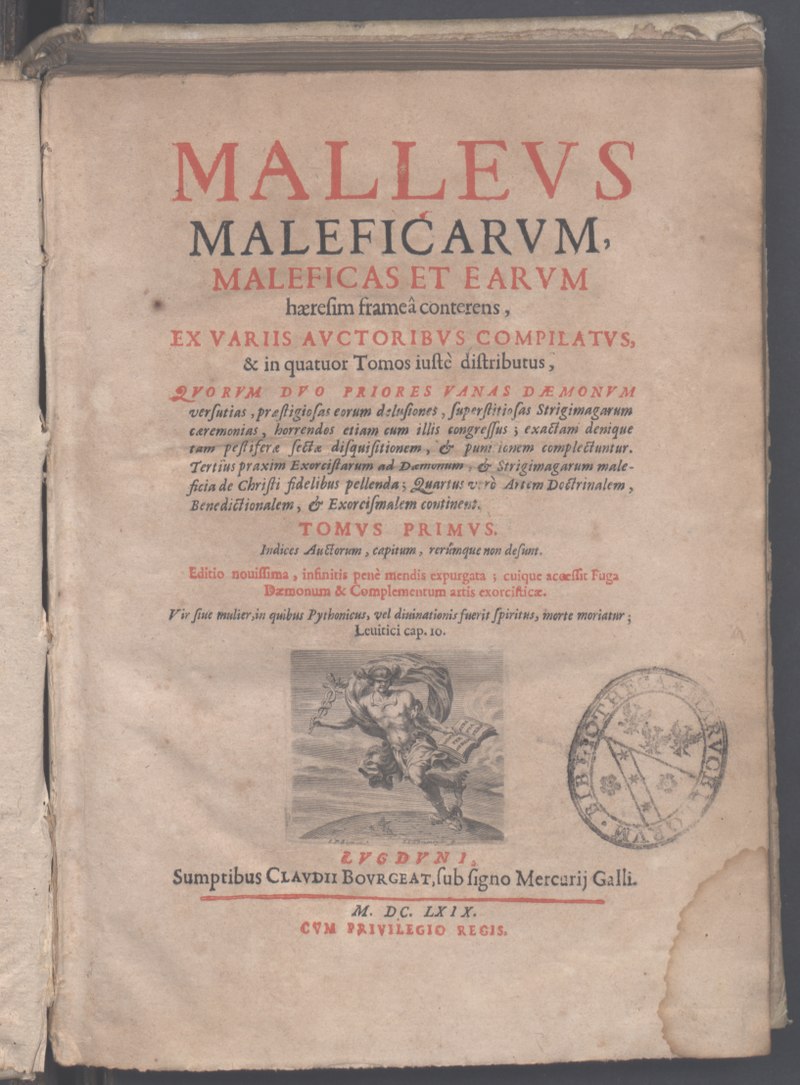

There were many witch hunters, and the most famous among them was the Dominican friar Heinrich Kramer, a papal inquisitor engaged in the fight against Waldensians, heretics, and Jews. The friar became known for co-authoring, with Jacob Sprenger, the 1487 treatise “Malleus Maleficarum“, the most renowned manual for witch hunting. However, Italian Humanist scholars and other European intellectuals worked against the persecutory activities, thus averting many massacres.

The Nature of the Accused

Often among the accused of witchcraft, some women suffered from mental or physical disorders. Merely having epilepsy or any psychophysical issue could risk sending you to the stake. These disorders also afflict Wanda, and indeed the Marvel Universe often deals with the problems caused by the unpredictability of her chaotic powers due to Scarlet’s psychological and emotional instability.

In this field, the work of the Dutch physician Johann Wier (1515-1588) was highly significant. In 1563, he wrote “De praestigiis daemonum et incantationibus, ac veneficiis” (On the Deceptions of Demons and Incantations, and Witchcraft). The treatise was published multiple times, sometimes with comments from colleagues who agreed that the behaviors of the “possessed” were actually due to neurological and psychological issues. With his medical knowledge, Wier asserted that the behaviors considered abnormal and thus associated with the devil were actually physical disorders and that no confession made under torture by the Inquisition could be deemed valid. By introducing what would later be known as “mental illness” into the proceedings, Wier managed to save the lives of many women.

The End of the Witch Burnings

“Witches stopped existing when we stopped burning them.”

Voltaire

The advent of European rationalism and the Illuminism also brought an end to the witch burnings in Europe. From the 15th century until the Age of Illuminism, the persecution in Europe and the American Colonies claimed about 50,000 lives. Witchcraft was decriminalized, and the killing of witches became illegal.

After the feminist movement of the 1970s, whose slogan was “Tremble, tremble! The witches are back!”, witches have indeed regained popularity in the collective imagination. Their stories appeal to the public when presented in a less demonic, yet still powerful and unsettling manner, just like our Scarlet Witch.

Sources

- Behringer W., Le Streghe, Il Mulino, 2008

- Duni M., I dubbi sulle streghe, in I vincoli della natura. Magia naturale e stregoneria nel Rinascimento, a cura di Germana Ernst e Guido Giglioni, Roma, Carocci, 2012, pp. 203-221

- Graf F., La magia nel mondo antico, Economica Laterza, 2009

- Gusso M., Streghe, folletti e lupi mannari nel Satyricon di Petronio, in Circolo Vittoriese di Ricerche Storiche – Quaderno n. 3 (settembre 1997), pp. 97-117

- Petronio Arbitro, Satyricon, BUR, 2013

Here you can find the italian version of this article.